Idaho Chief Justice calls for the eradication of flat fee contracts

Pleading the Sixth: On August 15, 2013, the Chief Justice of Idaho addressed a legislative committee charged with studying the need for state involvement in the oversight and administration of right to counsel services. Calling for the eradication of flat fee contracts, the Chief Justice advocated for a return to Idaho’s historical roots of providing for the effective assistance of counsel at public expense that long ago placed Idaho at the forefront of right to counsel jurisprudence in America.

“Our system for the defense of indigents, as required by Idaho’s constitution and laws, is broken,” declared Idaho’s Chief Justice, Roger Burdick, in a speech on August 15, 2013, kicking off the first meeting of a legislative committee charged with determining how best to overcome the state’s indigent systemic deficiencies, and as reported in the San Francisco Chronicle of the same day.

“I believe strongly that Idaho must aggressively improve the system that exists today,” continued the Chief Justice, offering a number of recommendations on which the legislature should reform right to counsel services. Preeminent in the Chief Justice’s recommendations to the committee is the charge to analyze the impact of what he called “low-bidder or fixed rate contracts.” In Idaho, the predominant method of delivering right to counsel services is for county governments to contract with the lowest bidder to provide representation in an unlimited number of cases for a single flat fee.

Attorneys working under fixed rate contracts are generally not reimbursed for overhead or for out-of-pocket case expenses, such as mileage, experts, investigators, etc. The more work an attorney does on a case, the less money that attorney would make, giving attorneys a clear financial incentive to do as little work on their cases as possible. Such contractual arrangements are banned under the American Bar Association, Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System (Principle 8). To Chief Justice Burdick, the conflict of interest is inherent in low bid, flat fee contracting and “must be eradicated.”

The Legislative Committee

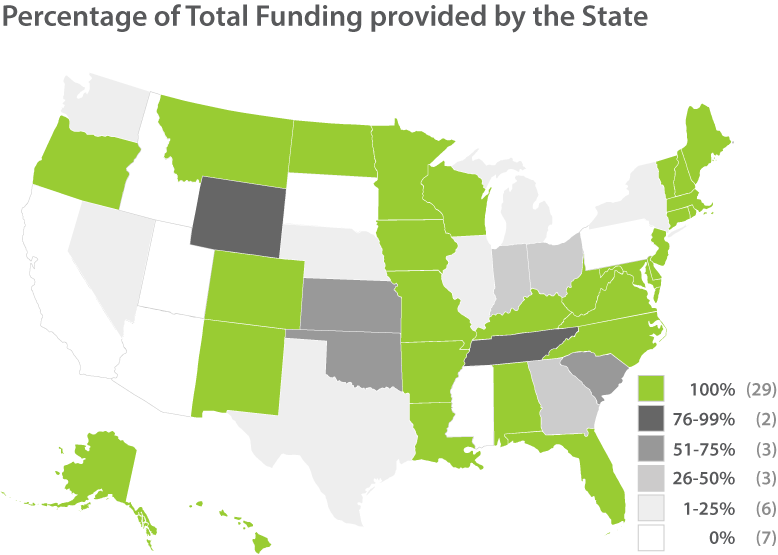

Though Gideon v. Wainwright, makes clear that the funding of indigent defense services is incumbent upon states (not counties) through the Fourteenth Amendment, Idaho remains one of only seven states that do not contribute any money for non-capital, trial-level right to counsel services. The others are Arizona, California, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Utah. To be clear, it is not believed to be unconstitutional for a state to delegate such responsibilities to local government. However, in doing so a state must guarantee that local governments are not only able to provide such services but that they are in fact doing so. Idaho has no such mechanism for evaluating the effectiveness of the county-based systems.

In the 2013 legislative session, the Idaho legislature took an incremental step to correct that by passing concurrent resolution HCR 026. The concurrent resolution acknowledges numerous systemic deficiencies in the delivery of the right to counsel in Idaho including, but not limited to, a lack of uniformity in the “appointment and waiver of counsel, contribution and recoupment practices, public defense contracting practices and data reporting; excessive caseloads and workloads; a lack of independence of the public defense function; a lack of training and resources for attorneys providing public defense services, particularly in the areas of juvenile defense, child protection and mental health commitment; the existence of flat fee contracts for public defense services; and county commissioners’ lack of access to information and resources to assist in the provision of public defense.”

The resolution goes on to state that the nationwide approach to overcoming such systemic deficiencies has been “state oversight of the public defense system that includes statewide standards and, in many instances, state moneys.” HCR 026 calls for a legislative study commission of five Senators and five members of the House to determine how best to move to state oversight.

One idea that is being given serious consideration was put forth by Kootenai County, Board of County Commission member Daniel Green in a letter to 6AC Executive Director, David Carroll on August 13, 2013, which was also presented to the legislative committee. Given the extreme difficulty Kootenai County Commissioners have had dealing with complex constitutional issues for which they have had no formal training, Mr. Green suggests that the committee should consider “a ‘reverse’ revenue sharing plan where the counties would fund a state indigent defense system by paying their prorated share to the state. The state could provide defense by county or districts.”

Conclusion

The Chief Justice also challenged the committee to look to existing state and national workload standards (ABA Principle 5) because effective representation starts with “time – time to interview, investigate and prepare legal arguments.” State and national workload standards need to be “made enforceable” throughout Idaho. And, fair and impartial trials require “competent attorneys who are trained” (Principle 9) and “have an experience level commensurate with the case or crime” (Principle 6).

Whatever the specific answer for Idaho turns out to be, the Chief Justice made sure that the legislative committee understood where the Court stood in relation to the state’s failure to protect children in delinquency and child protection cases. “Our judges tell us that in some counties, the newest attorneys are often assigned these cases, yet the complexity of the law and the vulnerability of the children represented require seasoned, well trained and capable attorneys,” he stated. The juvenile justice laws of Idaho can only be properly implemented “if qualified, trained lawyers are available” for kids.

The legislative committee will continue to work throughout the fall with the hopes of entering a sweeping indigent defense reform package in the 2014 session. The 6AC staff will keep you abreast of progress as it occurs in Idaho.