Report released evaluating the right to counsel in rural Nevada

Pleading the Sixth: Remote population centers across great geographic expanses, a paucity of attorneys, limited social services, almost no public transportation, restricted tax bases, and non-lawyer judges in misdemeanor courts, are just some of the problems states often face while trying to provide effective public defense services in rural America. These problems are exacerbated in rural Nevada, where only 333,373 people reside over an area that is larger than all but ten states. Add to that a troubled history causing local governments to distrust state government regarding provision of the right to counsel, political polarization of urban and rural viewpoints, and a state supreme court trying to remedy structural right to counsel deficiencies but constrained by separation of powers, and you have some of the most intractable indigent defense issues we have encountered. The 6AC details it all in a new report and updates you on the prospects for reform.

On September 4, 2018, the Sixth Amendment Center delivered the report, The Right to Counsel in Rural Nevada: Evaluation of Indigent Defense Services, to the Nevada Legislative Counsel Bureau. The report details for the first time how indigent defense services are provided in every trial level court outside of Clark County (Las Vegas) and Washoe County (Reno), collectively referred to in Nevada as the “rural counties,” and then assesses those services against prevailing standards and Sixth Amendment case law.

The report finds that there are longstanding, deep-rooted problems in the rural courts, including: a dearth of public defense data, especially regarding caseloads; a prevalence of fixed fee contracts; a pervasive lack of independence of the defense function from undue political and judicial interference; and the failure to appoint attorneys early enough in the criminal process. The municipal courts in Nevada are a cause of particular concern where some judges chill the right to counsel by informing defendants that they will be charged for the cost of their representation.

The evaluation was conducted on behalf of the Nevada Right to Counsel Commission (NRTCC), a study commission created by the 2017 legislature as a compromise after more comprehensive reforms stalled. Based in large part on the recommendations in the report, the NRTCC adopted its own legislative priorities.

We will explain it all.

Indigent defense in rural Nevada

Nevada has 16 counties and the one independent city of Carson City that is the state’s capital. For the purposes of this post we refer to a total of 17 counties. Two of the counties are markedly urban. Clark County includes Las Vegas and has a county population of 2,204,079. Washoe County includes Reno and has a county population of 460,587. Together, these two urban counties constitute nearly 89% of Nevada’s total population of 2,998,039, but they cover only 13% of the state’s geography. The other 87% of Nevada’s vast 109,781 square miles makes up the 15 counties that are home to only 11% of all Nevadans.

Only Clark County and Washoe County, each with a population of 100,000 or more, are required to have a county funded public defender office with a full-time public defender. All of the other counties may have a public defender office if they wish and their public defender does not have to be a full-time employee, i.e. the county can enter into a contract with a private attorney to serve as the public defender on a part-time basis.

Only the three rural counties of Elko, Humboldt, and Pershing have a county funded and administered public defender office, furnished and equipped at government expense and staffed by full-time government employees who receive a salary and benefits. Churchill, Douglas, Esmeralda, Eureka, Lander, Lincoln, Lyon, Mineral, Nye, and White Pine counties instead provide right to counsel services by contracting with private attorneys for a fixed annual fee and out of which the attorney must provide all overhead necessary to serve as an attorney. In many instances, these contract attorneys are also responsible for paying for much of the case-related expenses that are necessary to the defense of the indigent defendants whom they are appointed to represent.

If a county does not have a public defender office in some form, then the state public defender provides indigent representation in that county. Only Carson City and Storey County remain in the state public defender system. The counties in which the state public defender office provides trial level services must pay the state for those services in an amount assessed by the legislature in each biennial session, which since 1991 has been 100% of the estimated cost of trial level services. The state provides the funding for appeals handled by the state public defender office in all counties other than Clark and Washoe and for post-conviction statewide.

The problematic history of the State Public Defender

In 1971, Nevada created the Office of State Public Defender and, for the first time in Nevada’s history, appropriated some state funds toward the provision of the Sixth Amendment right to counsel. The legislation created a seven-member commission to select the state public defender. The state public defender was authorized to employ deputies and support staff and also to contract with private attorneys if needed. The main office was located in Carson City, and the state public defender was allowed to establish branch offices, each to be supervised by a deputy state public defender. The state public defender was to, upon appointment by a court, provide representation to indigent defendants charged with a gross misdemeanor or felony in any of the 15 rural counties that had not established a public defender office, and also to handle appeals and post-conviction proceedings out of all 17 counties.

Just as the state public defender office was being established, in 1972 the United States Supreme Court issued its opinion in Argersinger v. Hamlin, requiring the appointment of counsel to indigent defendants facing the loss of liberty in misdemeanor cases. Even as the Nevada legislature authorized the SPD to provide misdemeanor representation, the state also began requiring the rural counties to pay the state public defender for the representation provided.

The duties of the state public defender office expanded, yet the legislature continually diminished its independence. In 1977, the commission that had been established to select the state public defender was abolished, and the state public defender became a direct gubernatorial appointee. An evaluation of the SPD conducted between December 1979 and August 1980 found that the state public defender at the time “inherited a disorganized and underfunded office” characterized by: a lack of investigators and social workers; inexperienced attorneys; high turnover; a lack of money for experts and other trial-related expenses; little supervision; no training; no brief bank; late entry into cases (especially juvenile delinquency cases); inadequate record-keeping; a lack of independence from the judiciary; a lack of qualified attorneys to take eligible cases; and insufficient funding. (Abt Associates, The Nevada State Public Defender Office: A Preliminary Assessment at 4-5 (Aug. 1980).) The state public defender office lost all independence from the executive branch in 1993, when it became an office within the department of human resources and the state public defender was placed under the supervision of the governor and the director of the department of human resources.

In ensuing legislative sessions from 1973 to the present, the amount each rural county is required to pay to the state for the provision of right to counsel services has steadily increased. Looking toward FY1980, the state was funding only 20% of the overall costs of the state public defender office, while the rural counties that had not established their own county public defender office were collectively paying 80% of the total costs of state public defender office operations statewide. By 1991, the counties that used the state public defender office to provide trial level services were paying 100% of the cost of those services. This resulted in a slow exodus of the rural counties from purchasing right to counsel services from the state public defender.

The state supreme court reacted to the devolution of the SPD system with a series of administrative orders requiring, among things, standardized indigency determinations, attorney performance standards, removal of the judiciary from oversight of defender services, and the banning of certain types of flat fee contracts that require the attorney to pay for conflict representation out of his or her take home pay. However, the court does not have the power of the purse and cannot, because of separation of powers concerns, tell the legislature how to spend taxpayer resources.

In his 2017 State of the Judiciary address, Chief Justice Michael Cherry decried the growing justice gap in right to counsel services between urban and rural jurisdictions in Nevada. Announcing that rural counties simply cannot shoulder the state’s Sixth Amendment obligations any longer, the Chief Justice challenged the legislature to create a statewide indigent defense commission. “In our urban counties, a defendant can count on a public defender to provide prompt representation. However in the rural parts of our state, indigent defendants may sit in jail for an extended period of time waiting to speak to an attorney while witnesses’ memories fade and investigative leads go cold.” He continued, “even after that defendant is appointed an attorney [in a rural court], he or she may be one of several hundred clients all vying at the same time for the attention of that single attorney.”

Noting that the rural counties’ “financial burden increases as the U.S. Supreme Court continually clarifies and expands the obligations an attorney owes the indigent accused”and the systems in which they operate, Justice Cherry urged the legislature to engage in comprehensive reform. He said: “We must do better at providing representation to rural defendants. . . . Rural persons are just as deserving of representation as their urban neighbors. I encourage you to provide equal justice to rural individuals too. The time has come for an independent Indigent Defense Commission.”

During the 2017 legislature, a bill was filed that would have created a statewide commission with authority over the provision of the right to counsel in all of Nevada’s courts. Prospects for reform stalled when rural jurisdictions feared that state oversight meant the counties would be forced to use the services of the SPD again.

The assessment of rural services

Like every other state, the State of Nevada has a Fourteenth Amendment obligation to ensure effective Sixth Amendment services in every court at every level everywhere in the state. This means that the State of Nevada must, at the very least, have an entity authorized to promulgate and enforce systemic standards. No such entity currently exists. Moreover, the State of Nevada does not require uniform indigent defense data collection and reporting. Without objective and reliable data, right to counsel funding and policy decisions are subject to speculation, anecdotes and potentially even bias. For trial level services, the State of Nevada has only very limited oversight of primary representation (not conflict representation) in just the two jurisdictions (Carson City and Storey County) that use the state public defender office. Yet the state public defender system suffers from undue political interference and inadequate funding.

Thirteen of the 15 rural counties fund and administer local indigent defense structures based on the unique characteristics of their individual jurisdictions. Without guidance from the State of Nevada on how to create local structures that meet the parameters of the Sixth Amendment, the local indigent defense systems suffer to various degrees with:

- lack of independence from judges, prosecutors, and county/city governance;

- lack of institutionalized attorney supervision and training;

- absence of attorneys at initial appearance to advocate for pretrial release of defendants;

- lack of independent defense investigations in all but the most serious felony cases;

- almost no support services, such as social workers, legal secretaries/paraprofessionals, mental health services, and translation services for non-English speaking indigent defendants;

- fixed fee contracts that pay the same no matter how few or how many cases the attorney handles, and that require the attorney to pay for overhead out of the fixed compensation, and that in some instances require the attorney to pay for conflict counsel and/or case-related expenses out of the fixed compensation; and

- excessive caseloads in those rural counties with populations greater than 15,000.

Most rural cities and counties in theory require the public defense attorneys to report caseload information, but in many places the attorneys simply do not do so. Where attorneys do report this information, most cities and counties do not make any use of the data, at least in part because the data is not reported uniformly even among attorneys providing representation in the same jurisdiction. Even in those jurisdictions that try to use reported data to prevent excessive caseloads, it is impossible for local policymakers to gauge an attorney’s entire workload, because the State of Nevada does not track which attorneys are providing representation in multiple jurisdictions and which public defense attorneys are employed in other court functions (e.g., magistrates, prosecutors).

Rural counties and cities that administer and fund their own local indigent defense systems, for the most part, do not have standards for the selection of qualified attorneys with the experience to match the complexity of the cases to which they are assigned. While most rural attorneys appear to be qualified to handle the criminal cases to which they are appointed, this is serendipitous. There is nothing to prevent future local policymakers from hiring non-qualified lawyers offering the lowest cost to cover the greatest number of cases.

Layered on top of all of this are the vast geographical distances, the paucity of attorneys in many areas of the state, and the structure of Nevada’s courts and its procedures, which taken together seem to render it nearly impossible for the individual counties and cities alone to provide public defense systems that can ensure effective assistance of counsel. All of this results in:

- judges refusing to appoint counsel to misdemeanor defendants facing jail time where the judge predicts a suspended sentence;

- uncounseled defendants negotiating directly with prosecutors and then pleading guilty to misdemeanors, and doing so at initial appearance/arraignment;

- judges not adhering to the indigency determination procedures ordered by the Nevada Supreme Court, resulting in over-appointment and under-appointment (depending on jurisdiction);

- delays for indigent defendants in receiving appointed counsel and in the timely conclusion of the criminal proceedings against them;

- imposition of reimbursement of public defense costs on indigent defendants (along with other fines & fees) without determining a defendant’s ability to pay;

- judges sentencing convicted indigent defendants to pay fines & fees without determining their ability to pay, and attorneys failing to advocate on behalf of indigent defendants against imposition of these fines & fees.

Finally, although defendants have a right to appeal misdemeanor convictions from non-lawyer judge courts (justice courts and municipal courts) and to take that appeal to a district court where the judge is a lawyer, the appellate review is based solely on the record made in the court of the non-lawyer judge. These misdemeanor convictions most often result from cases where the defendant did not have a lawyer in the non-lawyer court to begin with. As a result, the defendant is on their own and incapable of making a defense, of making an appropriate record in the non-lawyer court, and of taking the necessary steps to obtain review by a court where the judge is a lawyer.

A word about municipal courts

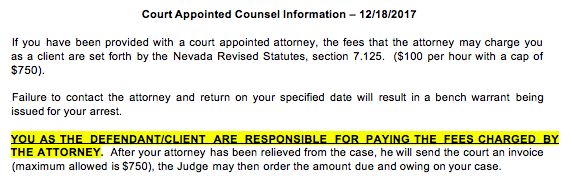

Cities receive almost no direction at all from the state about how to provide representation in the municipal courts to indigent defendants charged with misdemeanors that carry possible jail sentences. Municipal courts were found to be more likely to charge defendants the costs of public representation without conducting individualized colloquies on the record to determine if the defendant can afford to pay those costs.

For example, the Ely Justice Court routinely assesses $85 per hour of a public defender’s time against indigent defendants, and the Yerington Municipal Court assesses a flat $250 charge against every defendant who seeks a public defender. These practices chill the right to counsel. During our first court observation in the Yerington Municipal Court, three of the first five defendants, all of whom were facing jailable offenses, waived their right to counsel after being advised that counsel would cost them $250.

Although the 6AC was not charged with studying the municipal courts within Clark and Washoe counties, we did reach out to these courts to determine which lawyers are providing representation there. In correspondence with the Boulder City Municipal Court, the court sent us a document that reads in part:

Moving forward

There is no pre-existing, uniform cookie-cutter indigent defense service delivery model that states must apply. The question for Nevada policymakers, in conjunction with criminal justice stakeholders and the broader citizenry of the state, is simply how best to fulfill the Sixth Amendment guarantee of the right to counsel, given the uniqueness of the state. Culminating the evaluation, 6AC makes the following recommendations to serve as a guide for Nevada policymakers in reaching Nevada-specific answers to overcome the systemic deficiencies highlighted in the report.

- The State of Nevada should create a permanent Board of Indigent Defense Services (BIDS). BIDS will provide advice and guidance to an executive branch organization, the Office of Indigent Defense Services (OIDS), to oversee the provision of defender services in the state.

- The State of Nevada should authorize OIDS to promulgate standards including, but not limited to: a) attorney qualifications; b) attorney training; c) early appointment of counsel; d) attorney supervision; e) attorney workload; f) uniform data collection and reporting; and g) contracting. Standards should undergo a public comment period and be approved by an official branch of government.

- Local governments should be authorized to select the method of delivering indigent defense services that most appropriately serves their local needs. When the Office of Indigent Defense Services (OIDS) promulgates a new standard, and it is approved under Nevada regulatory practices, local governments should be given a set reasonable amount of time to create and submit plans to the OIDS regarding: a) how their localized systems intend to meet said standard; and b) the associated budget to meet the standard. If plans are approved by OIDS, all new spending to meet said standards should come from the state and not local governments.

- OIDS should additionally: a) qualify, train, and supervise attorneys that local governments may contractually engage; b) conduct on-going system evaluations against standards; c) review, approve, and fund requests for trial-related expenses (investigators and experts); and d) collect uniform data. OIDS should also oversee the State Public Defender office. The State Public Defender’s appellate responsibilities should be expanded to include direct appeals.

- The Nevada Supreme Court should adopt an administrative rule specifically requiring all courts to conduct on the record individualized colloquies using the court ordered indigency standard to determine if a defendant can afford to reimburse government all or a part of their indigent defense representation if a court elects to impose public defense recoupment fees. OIDS should be statutorily authorized to collect data on assessments and recoupments and to conduct assessments to see that the practice is correctly followed.

- The Nevada Legislature should create a student loan forgiveness program to encourage young lawyers to serve as public defenders in those counties with less than 100,000 populations.

The Nevada Right to Counsel Commission (NRTCC) accepted these recommendations with one notable exception. Rather than create a new commission, the members of the NRTCC decided that they worked well together and had a balance between the interests of the state and local governments, the interests of rural communities and urban jurisdictions, and the interests of the three branches of government.