Should non-lawyer judges be sending people to jail? SCOTUS asked to review

Pleading the Sixth: In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that the Fourteenth Amendment permits non-lawyer judges to impose jail time so long as the defendant has the ability to get a do-over in front of a judge who is a lawyer. Now the Court is asked to clarify whether due process concerns allow non-lawyer judges to send defendants to jail without having a new trial with a judge who is a lawyer. As the Court considers the petition for cert filed by the Montana Office of the Appellate Defender and the UCLA School of Law on the question, the 6AC explores the impact non-lawyer judges have on the denial of counsel in misdemeanor courts.

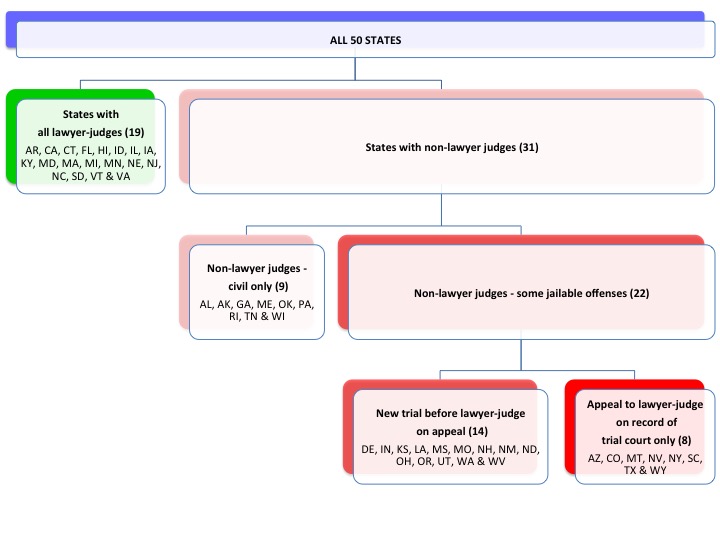

Though it may seem surprising that judges in all of America’s courts do not necessarily need to be lawyers, the practice is fairly common. Thirty-one states have some courts where judges do not have to be a lawyer (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming). In nine of these states that allow non-lawyer judges, along with the 19 states and the District of Columbia that require all judges to be a lawyer, the non-lawyer judges are banned from taking a defendant’s liberty in a criminal proceeding.

(The 6AC thanks the Montana Office of Appellate Defender and the UCLA School of Law for letting us share their research from their petition for cert. Wholly banning non-lawyer judges from presiding over the trial of a misdemeanor or ordinance that carries jail time are: Alabama, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, and Virginia. Additionally, in Alaska and Wisconsin, a non-lawyer judge may only try a defendant in a criminal proceeding with a potential for incarceration if the defendant consents to doing so, and in Georgia, a non-lawyer judge may only try a defendant in a criminal proceeding with the potential for incarceration if the defendant waives his right to a trial by jury.)

The remaining 22 states, primarily for reasons of cost efficiency or to facilitate justice in more rural jurisdictions, have non-lawyer judges preside over misdemeanors or ordinances that carry jail time as a possible punishment. But even among those states, 14 of them give the defendant the right to have a trial de novo on appeal – basically a whole new trial – before a judge who is a lawyer (Delaware, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and West Virginia (unless in West Virginia the defendant had a jury trial)). That leaves the eight states — Arizona, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, New York, South Carolina, Texas, and Wyoming — where a defendant can stand trial before a non-lawyer judge on a jailable offense, and if he is convicted and sentenced to jail, his only recourse is to appeal to a higher court with a judge who is a lawyer. But that appeal is based solely on whatever record was made in the non-lawyer court; he does not get a new trial.

As explained in the Montana cert petition, “In North v. Russell, 427 U.S. 328 (1976), the Court held that the Due Process Clause permits a criminal defendant facing the possibility of incarceration to be tried by a non-lawyer judge — so long as the defendant has the right to a de novo trial before a judge who is a lawyer.” But the U.S. Supreme Court has never decided whether it is okay for a defendant to be tried by a non-lawyer judge where a state does not give the defendant a new trial on the appeal to a court whose judge is a lawyer. And that is the issue that the Montana lawyers are seeking to have the U.S. Supreme Court decide.

Sixth Amendment Implications

So what does this all mean for the Sixth Amendment right to counsel? First, if the indigent accused is facing jail as a penalty before a non-lawyer judge and is fortunate enough to receive a public defense attorney, that lawyer is trying to argue complex legal issues to a non-lawyer. Let’s say for example that the defendant is entitled to a jury trial, as he is in some of these courts and cases. Selecting a jury involves complicated legal issues about: what the lawyers can ask the potential jurors when selecting them; the reasons a potential juror can or must be struck from the jury; the evidence that can be presented to the jury; and the law the jury must follow to reach a verdict. Even judges who are lawyers often struggle to get the right answers to these questions. Will a non-lawyer judge have the legal knowledge to make rulings that comply with statutes and the Constitution?

Now imagine that all of this happens in a no record court, where there is no written or oral recording of what happened at the trial held by the non-lawyer judge. In an appeal to a higher court presided over by a judge who is a lawyer, if the defendant does not get a new trial with the appeal, the only way the higher court can review whether the defendant got a fair trial is for everyone to try to tell that appellate court what happened down below based solely on their memory or their notes. And of course the prosecutor and defense attorney and non-lawyer judge’s memories may not agree with each other.

But as Senator Grassley (R-IA), Chairman of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, has noted, and the 6AC has reported, the likelihood of an indigent defendant getting an attorney in a misdemeanor proceeding is severely limited. So an uncounselled defendant faces numerous hurdles that become increasingly difficult to surmount in front of a non-lawyer judge.

For example, non-lawyer judges often incorrectly think that, so long as there is no imminent threat of jail time, the court does not have to appoint counsel to the accused. In these cases, the non-lawyer judge sometimes tells a defendant that he does not get a lawyer because, if he is found guilty, he will only receive a “suspended” jail sentence. That is, the defendant can potentially be sent to jail, but he will remain at liberty after he is sentenced so long as he completes all duties and pays all fees imposed by the court. Yet if the defendant does not timely fulfill all of the terms of his probation, he can be re-arrested and brought to answer before the court. If determined to have broken his probation, the defendant’s liberty can be revoked and he will be sent to jail. In 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court prohibited this very practice, but it is still prevalent in no counsel misdemeanor courts. (See for example the 6AC Utah report).

Additionally, non-lawyer judges may, in violation of the Constitution, tell a poor person that she can only get a lawyer if she pays the government for part or all of the cost of that representation. Chances are high that the defendant will forgo an attorney rather than incur debt she cannot afford to pay.

Over my career, I have often observed non-lawyer judges pressure defendants into guilty pleas. Following their arrest, most people are brought to a police station or detention center for processing, and then the defendant is supposed to be brought before a judicial officer to determine whether or not he should be released pending further court action. In 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that the right to counsel attaches the first time a defendant is brought before a judge or magistrate. From that point forward, a court cannot proceed with any critical stage of the case without offering counsel to the poor defendant. (The 6AC wrote a whole report on these requirements.) Despite this, non-lawyer judges often require uncounselled defendants to meet with a prosecutor to try to settle the case before they will appoint a lawyer to represent an indigent person

Perhaps most glaringly, non-lawyer judges often fail to ensure that a defendant’s choice to proceed without a lawyer is an intelligent, knowing, and voluntary choice, as required by the Constitution. If a defendant is in jail waiting to go to court, prosecutors may offer the defendant a chance to get out of jail for time served if the accused simply pleads guilty. Of course, the defendant may jump at the opportunity to get out of jail. He may want to get back to family, or he might be afraid of losing his job. But he may not be aware of valid defenses he loses by taking the quick plea deal. That is why courts are constitutionally required to make individualized inquiries to determine whether a defendant is intelligently waiving his right to counsel. Non-lawyer judges, however, often attempt to determine the validity of a waiver of the right to counsel simply by asking the defendant: “Do you make this decision knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently?” Offloading this standard onto the defendant to make a determination for his self, though, cannot meet the constitutional threshold. After all, if the defendant is, in fact, not capable of making an intelligent choice with respect to his constitutional rights, how then could he intelligently respond to a judge’s question?

And, even in those jurisdictions that allow for a do-over before a lawyer-judge on appeal, a defendant must assert her desire to do so. But without counsel to advise them of this procedure, poor defendants simply do not know how to get a higher court to take a second look. For example, in 2013, there were 79,730 total misdemeanors and misdemeanor DUI cases heard in all justice courts statewide in Utah, but only 711 of such cases were reviewed de novo in all district courts combined (an appellate rate of 0.89%).

The problems of having non-lawyer judges in criminal proceedings can even impact felony charges. Though every state in the nation precludes non-lawyer judges from determining guilt and imposing prison sentences in felony cases, the initial stages of felony cases can and do begin in the lower courts overseen by non-lawyer judges in many states. In Mississippi, for example, felonies begin in municipal and justice courts, where non-lawyer judges may be responsible for issuing arrest warrants, presiding over initial appearances, and making decisions about bail, the appointment of counsel, and whether there is enough probable cause to bind the case over for prosecution in the higher court.

Conclusion

It is not that non-lawyer judges are intentionally trying to undermine the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments, nor are they consciously trying to put poor people in jail unduly. Indeed, many non-lawyer judges I have met are individuals who care deeply about justice and are trying to give back to their communities by serving part-time in this capacity. It is simply that it is difficult at best for part-time non-lawyer judges to keep abreast of ever-evolving Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment law.

As I wrote this piece, I thought back to a story that highlights the dangers of having non-lawyer judges preside over jailable misdemeanors. In 2003, while in the employ of the National Legal Aid and Defender Association, I was evaluating indigent defense services in Montana. My flight was delayed by snow and I arrived much later in the day than expected. Venturing down to the Missoula Justice Court to see if any court was still in session, I found myself in the court of a non-lawyer judge. An older gentleman was accused of stealing firewood. He did not have a lawyer representing him. When asked by the non-lawyer judge if he did it, the defendant told the court that he stole the wood to keep his family warm. Then, the non-lawyer judge asked the district attorney if he had any questions of the defendant. The prosecutor asked the defendant whether he had ever stolen firewood before. The non-lawyer judge did not inform the defendant that he did not have to answer the question, and the defendant said he had indeed stolen wood before from the same place on earlier occasions. Defendants do things for a variety of reasons and perhaps this defendant thought the judge and prosecutor would appreciate his honesty and that he was taking responsibility for his actions. Instead, the district attorney amended the complaint to also charge the defendant with the supposed earlier crime, triggering jail time, increased fines, and additional restitution, all despite the fact that no evidence had been presented that the alleged earlier incidents even occurred. The judge never asked if the defendant wanted counsel nor informed him of possible collateral consequences to pleading guilty.

The U.S. Supreme Court may or may not take up the Montana writ. But states are free to provide greater protection of individual rights than the minimum rights guaranteed by the national Constitution. The 6AC strongly urges all state legislatures to eliminate the practice of non-lawyer judges presiding over criminal cases for which defendants may be sentenced to jail.