The criminalization of poverty: a spotlight on South Dakota

Pleading the Sixth: When states make counties wholly responsible for the delivery of trial-level indigent defense services without state oversight of those services, bad things can and do happen. In this two-part report, the 6AC looks at South Dakota’s decentralized right to counsel system, and the resulting impact on the client community. Part I examines South Dakota’s criminalization of poverty through its unconstitutional public counsel cost recoupment practices. Part II explores why it is so important that the ABA Ten Principles be adopted in whole, through a discussion of how South Dakota’s assigned counsel compensation scheme – a scheme that is in some ways a model for the rest of the country – is contributing to inadequate representation and exacerbating the problems discussed in Part I.

The Sixth Amendment was established as a check against government tyranny over the liberty of the individual. Yet in South Dakota, exerting that constitutional privilege may be the very thing that ends up getting one’s liberty taken away for failure to pay for a basic constitutional right.

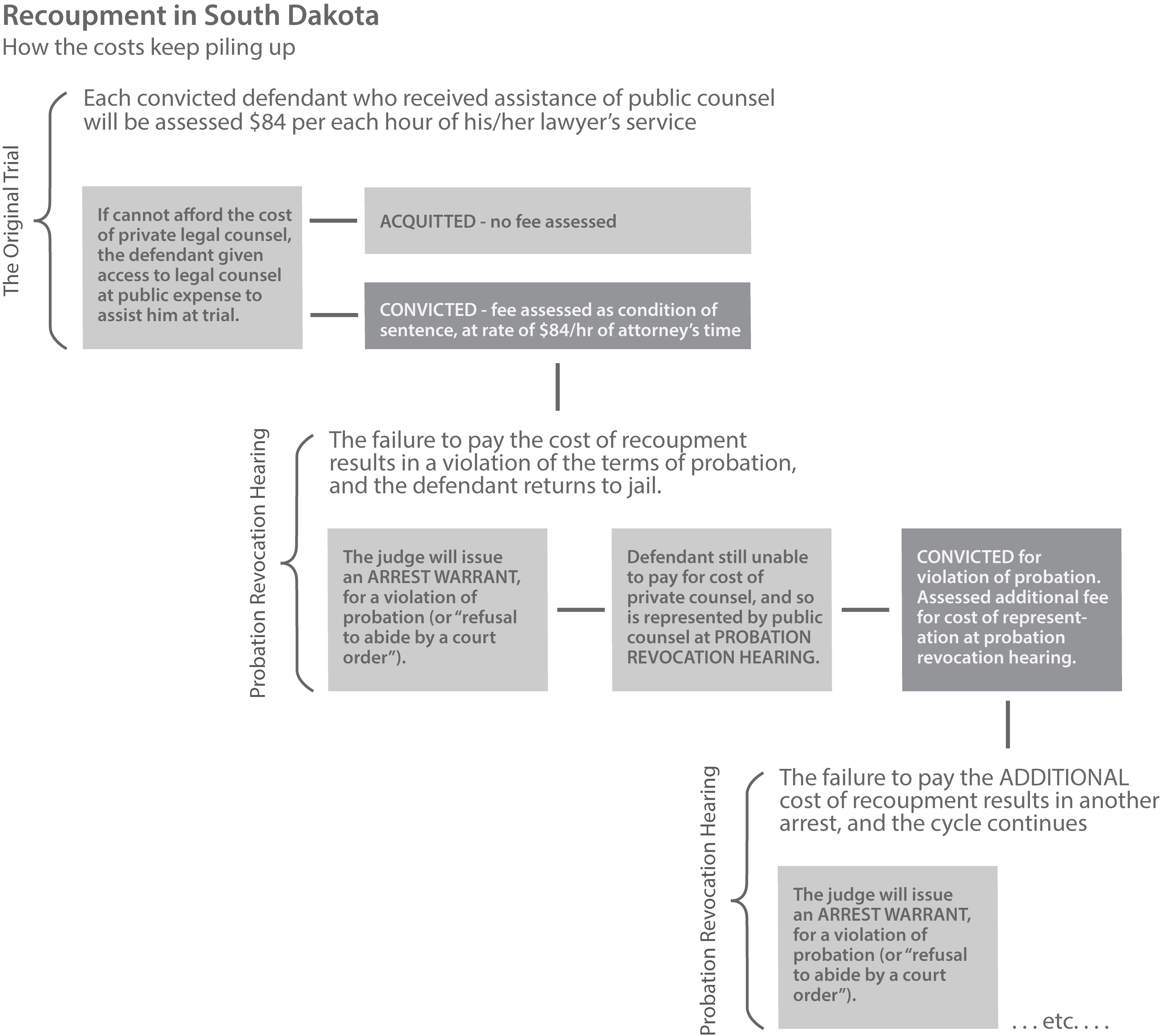

Every conviction of an indigent defendant in South Dakota results in the uniform assessment of court-appointed attorney fees at a set rate of $84.00 per hour. The recoupment fee is made a condition of the sentence, meaning that if a defendant is unable to pay, a warrant is issued for his arrest. When the indigent defendant is arrested on that warrant, he will be held pre-trial at taxpayer expense, appointed a second public attorney to represent him in the probation violation, potentially be incarcerated for failure to pay the cost of his first public attorney, and leave the court in any event with a new bill for the cost of his second attorney. (See graphic below.)

Poor people in South Dakota’s criminal justice system are often unable to break the cycle of poverty, as the downward financial spiral continues when the defendant is unable to pay this second bill and a new warrant is issued. Incarceration, even for a short stay, can have far reaching collateral consequences on a person of insubstantial means. Many will lose access to public housing, loss of disability pay, inaccessibility to student loans and/or veteran’s healthcare networks, to name just a few. Any one of these consequences will make it even more unlikely that a defendant can somehow prioritize paying back a county for the cost of his indigent defense representation over the most basic daily life’s needs.

(For an explanation on why South Dakota’s recoupment rate is set at the $84/hour figure, see Part II of the story.)

Indigent defense in South Dakota

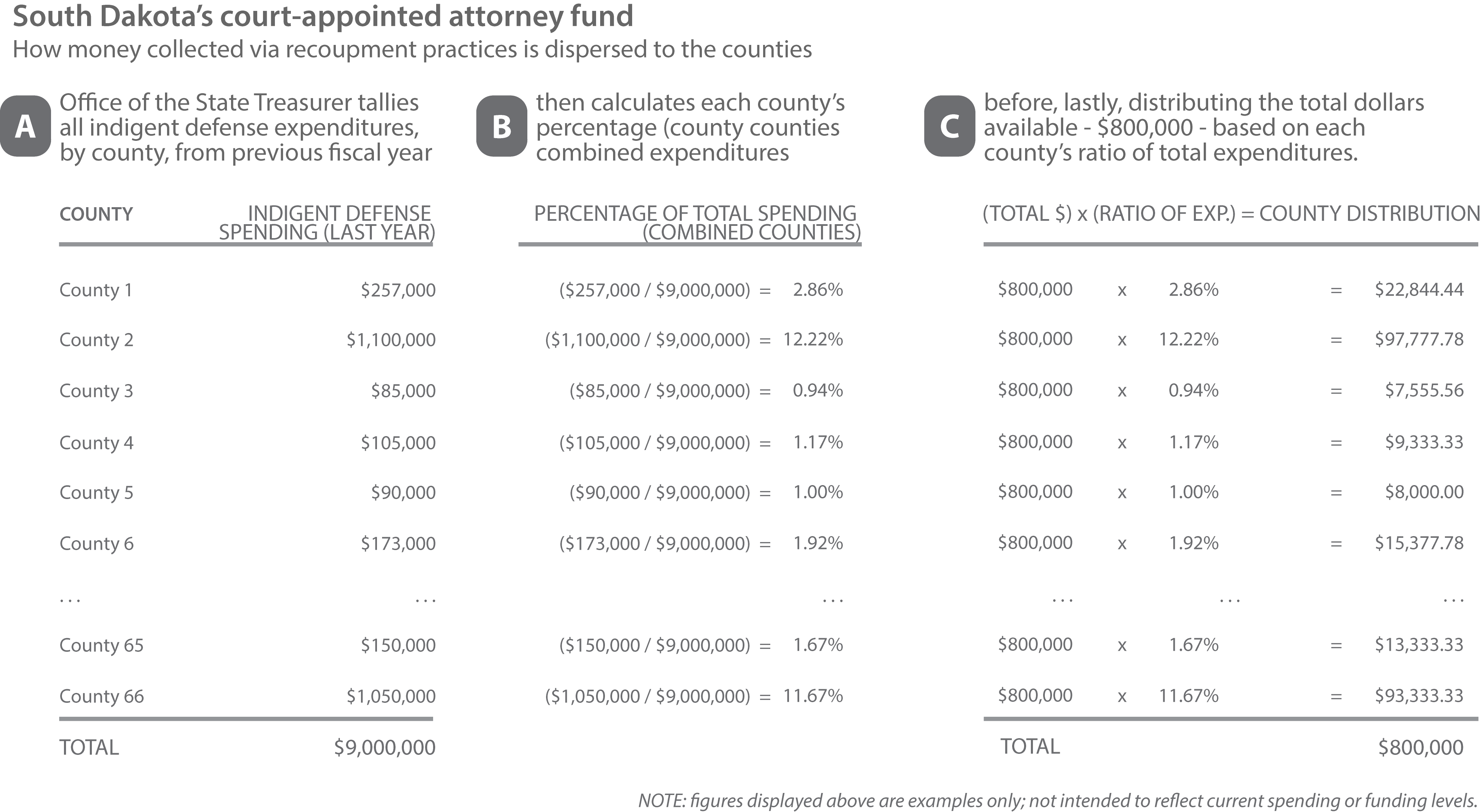

How does imprisonment for debt occur in America in 2013? It starts with the fact that the State of South Dakota has no involvement in the oversight of indigent defense services and very limited involvement in the funding of the right to counsel. In 1982, SDCL 23A-40-17 established a court appointed attorney and public defender fund in the Office of the State Treasurer. Historically, no state general fund appropriation goes to the public defense fund. Rather, a small percentage of a fee assessed on all criminal convictions is dedicated to the fund. SDCL 23A-40-20 requires that all moneys in the fund to be distributed annually on a pro rata basis to offset the counties’ indigent defense costs. This is basically just a math problem whereby the Office of the State Treasurer reviews the expenditures from all 66 of South Dakota’s counties and divvies up whatever little money is in the fund by the same ratio as the overall county by county indigent defense expenditures.

The vast majority of South Dakota’s counties rely on private attorneys for indigent defense services, with only three counties electing the public defender model [in Lawrence County (Spearfish), Minnehaha County (Sioux Falls), and Pennington County (Rapid City)]. Wherever the caseload can support a public defender office, it has often been found that public defender offices provide more cost efficient services. But, of course, indigent defendants are still charged the uniform $84/hour assigned counsel rate regardless of the actual expense of their public defender representation.

What national standards say about recoupment practices

Assessing the full costs of indigent defense representation, as done in South Dakota, violates the National Legal Aid & Defender Association Guidelines for Legal Defense Systems in the United States, Standard 1.7 on partial eligibility. Standard 1.7 states that a defendant should be asked to pay a “limited cash contribution” only if doing so does not impose a “substantial hardship upon himself or his dependents.” And, the fee should never exceed “ten percent of the total maximum amount” of what the cost of the local assigned counsel rate multiplied by the actual hours spent on the case. (So in South Dakota, the maximum fee to any defendant under the NLADA standard would be $8.40 per hour of representation.)

Furthermore, the American Bar Association, Standards for Criminal Justice, Providing Defense Services, Standard 5-7.2 states unequivocally that “[r]eimbursement of counsel … should not be required, except on the ground of fraud in obtaining the determination of eligibility.” To the extent that someone is found “partially eligible” (i.e., the defendant has some ability to pay some portion of his representation), ABA Standard 5-7.2 bars recoupment unless “satisfactory procedural safeguards are provided.” The term “satisfactory procedural safeguards” refers to the types of rules the United States Supreme Court relied upon in determining whether a state’s indigent defense recoupment plan meets constitutional muster in Fuller v. Oregon, 417 U.S. 40 (1974). In Fuller, the United States Supreme Court let stand Oregon’s recoupment statute because of the “safeguards” built in to prevent the imprisoning of defendants solely for failing to pay a Sixth Amendment incurred debt. Under Fuller, defendants with no likelihood of ever paying should not even be conditionally obligated to pay back the cost of their representation.

In 2004, the ABA House of Delegates adopted its Guidelines on Contribution Fees for Costs of Counsel in Criminal Cases to delineate what policymakers must do if they want to construct a recoupment policy that stays within Fuller’s procedural safeguards. Echoing Fuller’s demand that indigent defense cost recovery not impose a “substantial hardship” on the defendant, the ABA Guidelines goes on to state that whenever a cost recovery order is under consideration “the accused person or counsel should be given an opportunity to be heard and to present information, including witnesses, concerning whether the fee can be afforded.” This is a critical step that is not done in South Dakota. Most importantly, the ABA Guidelines prohibit either the denial of counsel or imprisonment, at any stage of the proceeding, for failure to pay a contribution fee. As the commentary to the ABA Guidelines notes the prohibition against imprisonment for failure to pay is rooted in the “unsuitability of imprisonment as an enforcement mechanism given the substantial cost in terms of liberty deprivation compared to the minimal benefit of extracting a nominal sum.”

Back to South Dakota

It is not surprising that states such as South Dakota are not in compliance with United States Supreme Court case law regarding indigent defense cost recoupment. The U.S. Supreme Court frequently rules on some aspect of the right to counsel but then it takes a series of state cases, and potentially further federal court cases, to make them take effect. For example, it is possible to go into almost any misdemeanor court room in almost any state and see daily violations of Argersinger v. Hamlin (the right to an attorney in misdemeanor cases), Shelton v. Alabama (the right to an attorney in cases with suspended sentences), and Rothgery v. Gillespie County (the right to an attorney at hearings where a defendant learns of the charges against him and where is liberty is at stake).

What is unique about South Dakota is that there are two state supreme court cases where the Court appears to just sidestep Fuller altogether. (See: State v. Huth, 334 NW2d 485, and White Eagle v. State, 280 NW2d 659.) In these cases, the South Dakota Supreme Court concludes that the jailing of people for failure to pay is not a Fuller v. Oregon violation, because the revocation of a suspended sentence for non-payment of attorney fees is not imprisonment for a debt. Instead, it is a “sanction for refusal to abide by a court order.” Whatever the South Dakota Court wants to call it, the criminal justice system in that state is putting people in prison for no other reason than that they are too poor to afford an adequate defense.